London (28/05 – 40.00) No one knows who put it here. But something rather odd has appeared in the centre of St Petersburg.

A bizarre art installation made up of one word: “ZAMESTIM” (“We will replace”).

Each letter is the first letter of an international brand that has suspended operations in Russia. Their company logos are featured, too.

Z is for Zara. A is for Adidas. M means McDonald’s…

Hundreds of international companies have pulled out of Russia in protest at the Kremlin’s offensive in Ukraine. Officials here have been trying to sound upbeat, claiming that Russia will find local replacements for foreign items no longer available.

But the disappearance of global products and services adds to Russia’s growing sense of international isolation.

That seems a strange thing to be saying in St Petersburg. After all, Emperor Peter the Great designed and built this city to make Russia feel like a part of Europe.

Out of marshland he created a breathtakingly beautiful Russian Amsterdam or Venice, with myriad canals and stunning palaces.

With the help of European artists and architects rose an imperial capital with a European face. Yet three centuries on, the gulf between Russia and Europe grows wider by the day.

Do Russians care? Many here claim not to.

“Russia’s not Europe. Russia is Russia,” says Lubov, who has stopped to chat to me by the “ZAMESTIM” art installation. Lubov tells me she doesn’t follow what’s happening in Ukraine.

“It’s an unpleasant news story,” she says. “So, I try not to watch TV. So that I don’t get upset.”

My next conversation next to “ZAMESTIM” is with Raisa. She gets all her news from Russian TV.

“The Ukrainians are to blame for the violence,” Raisa says. “They’re ganging up on us. Those nationalists are deploying weapons on our border. How certain are you that what Russian TV is telling you is the truth?” I ask.

“Knowing the Russian people like I do, I’m 100% sure.”

How many Raisas are there in Russia? What percentage of the Russian public support what President Putin calls his “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine?

More than 80%, according to recent surveys. I’m sceptical. In an authoritarian country like Russia, the accuracy of public opinion polling is questionable. Fear skews results.

Over the past two months, most of the Russians we have approached on the streets for interview have declined to speak about Ukraine, preferring to keep their opinions to themselves. Of those who did express views on the record, many repeated almost word for word what state TV has been telling them, reproducing the parallel reality created by the Kremlin.

They speak of Russian troops “liberating Ukraine” and “fighting Nazism in Ukraine.”

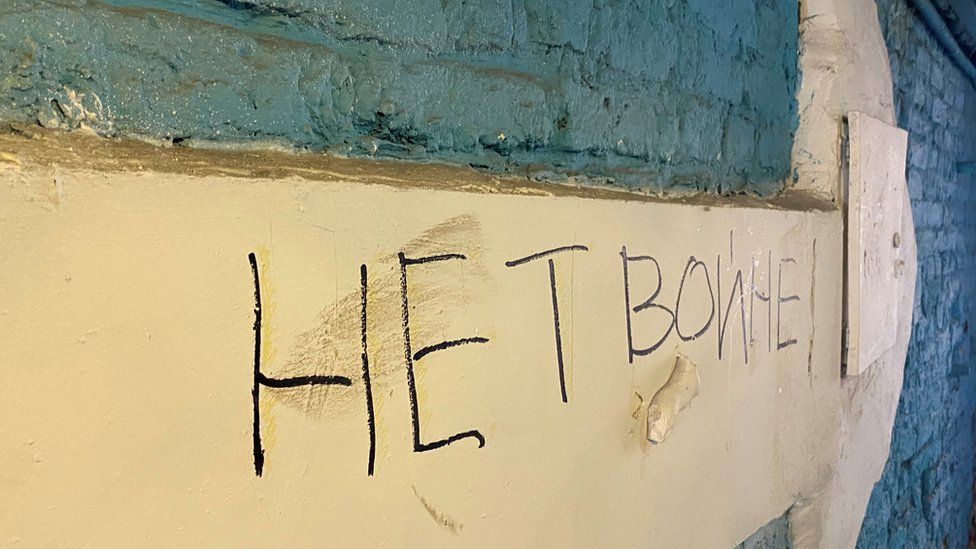

But when I take a stroll through the historic centre of St Petersburg, I discover a very different picture. Among the city’s famous courtyards, I find plenty of anti-war graffiti. In some cases, anti-Putin slogans, too, have been scrawled on walls.

There are other forms of protest. Earlier this month St Petersburg artist Sasha Skochilenko was arrested and charged with spreading fake news about the Russian armed forces. She is accused of replacing price tags in a supermarket with anti-war messages. Sasha is being held in pre-trial detention.

“This shows that free speech in our country is being stamped out,” Sasha Skochilenko’s partner, Sonia Subbotina, tells me. “It shows that political repression is getting worse and that people with anti-war views are being persecuted and put in prison.”

“There was protest activity in Russia. People were coming out to protest. But each protest is a major risk. You can be arrested, you can be beaten, you can be put in jail. Right now I feel completely lost. I don’t know if anything can be done.”

Those in power in Russia are demanding unflinching support from the Russian people: for the direction in which the Kremlin is taking Russia, away from Europe; for the anti-Western rhetoric emanating from Moscow; and for Russia’s military offensive in Ukraine – no matter what the consequences here at home.